Anna Schubertová

Abstract:

The Prolific Ambivalence of the Utopian Form

The utopian form, as it has been developed throughout the last centuries in literature, political thought, philosophy, and popular culture, continues to flourish despite repeated proclamations of its death. There is something in this form that continues to capture the interest of modern intellectuals from Thomas More, the humanist Renaissance thinker who believed that through a rational approach one could make society better, to Fredric Jameson, the Marxist postmodern theorist of late capitalism who conveyed the claustrophobic feelings in the seemingly static and unchangeable nature of our times. The aim of this paper is to explore possible reasons for the enduring relevance of the utopian form. One way to understand the powerful impact of the form is by highlighting its adaptability to different ideological and historical contexts can be linked to its fundamental ambivalence, glimpsing through the genre’s history and transformations, and within the foundational text of Utopia itself.

The Ambivalent Genre

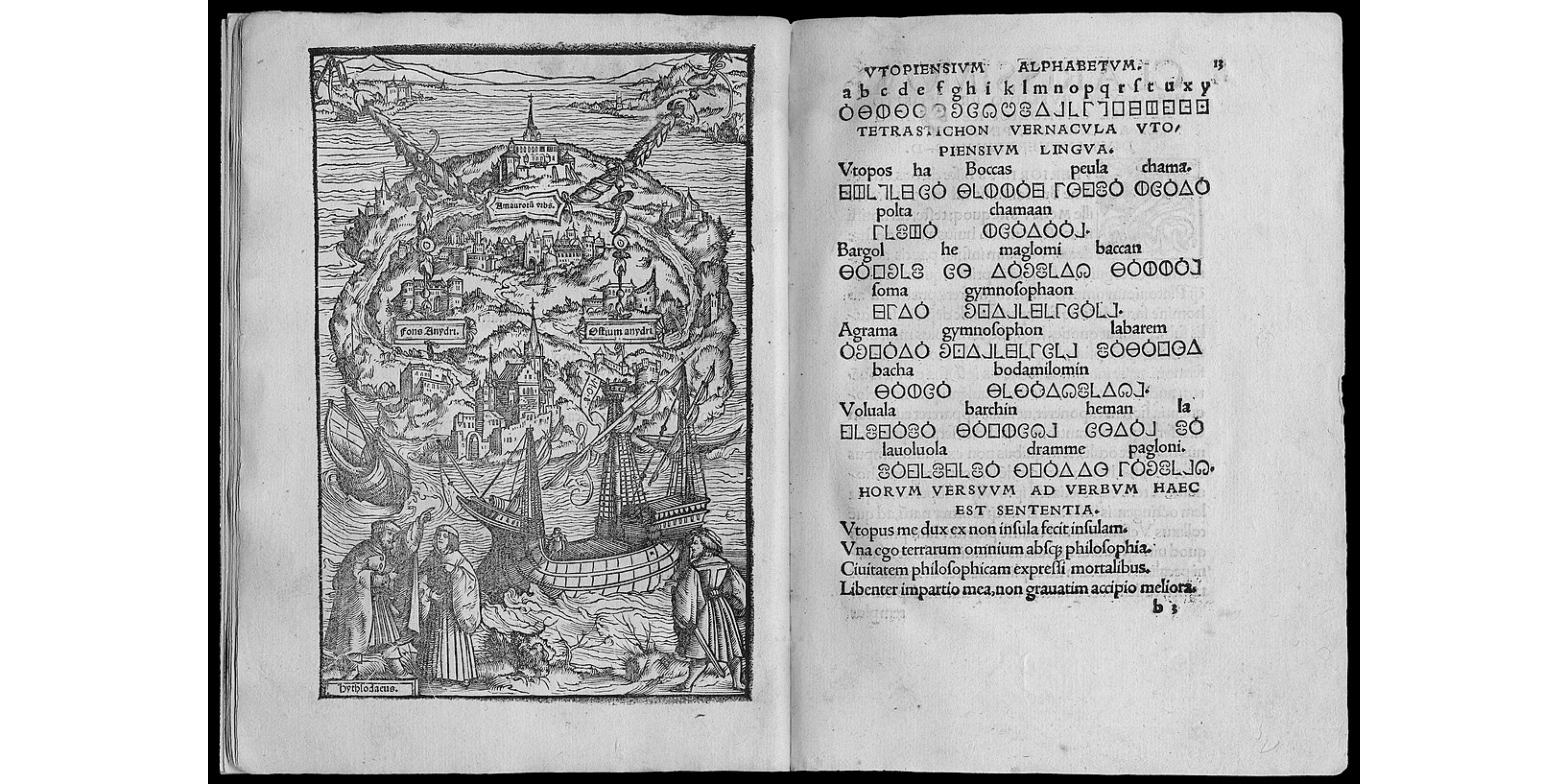

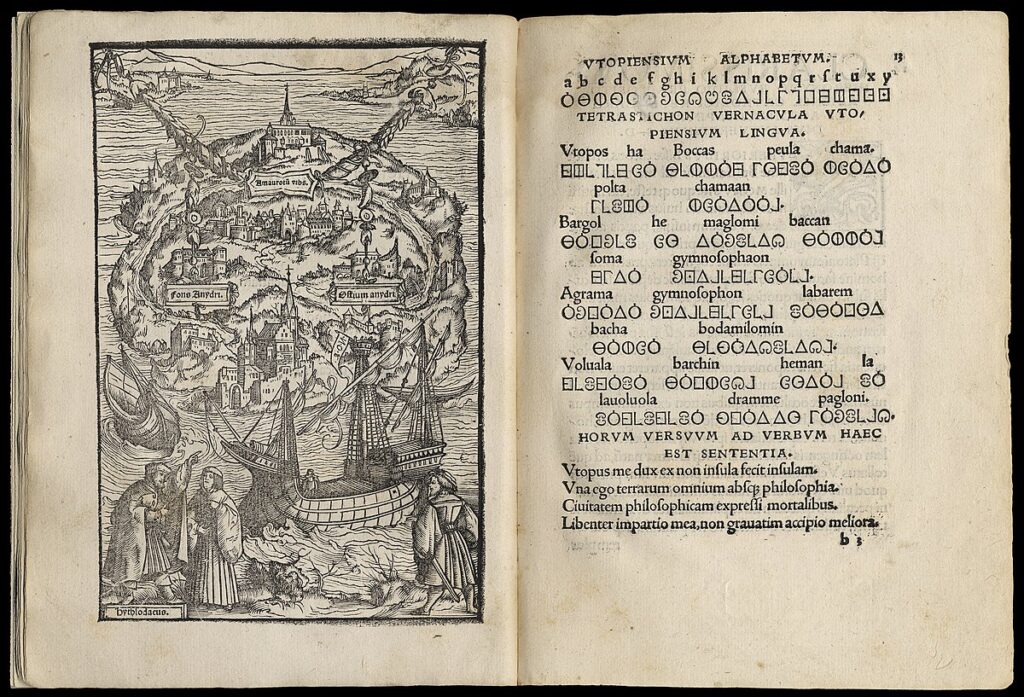

Defining utopia as a genre is easy in some respects and challenging in others. Not many genres have the same clarity regarding their birth dates as utopia does with Thomas More’s 1520 Utopia. While More’s Utopia has not been the first cultural artefact to imagine a different societal organisation, the text seemed to have captured modern imagination in a way that continues to inspire writers from different eras, ideological orientations, and disciplines. More’s foundational text opened the door to the utopian imagination not only by inventing the term “utopia” but also by inaugurating questions and dilemmas that will accompany the genre through its transformations up until now. In his Archaeologies of the Future (2005), Fredric Jameson argues that as a genre, utopia is singular in the way that its new iterations refer to previous utopian constructions, suggesting that “what uniquely characterises this genre is its explicit intertextuality: few other literary forms have so brazenly affirmed themselves as argument and counterargument” (Jameson 2005: 2). Given the strong intertextual nature of utopias and their relatably stable form, the contours of utopian progeny should be relatively easy to map out. However, the proliferation of utopian texts, imaginations, and forms has complicated the matter. To use a metaphor, the development of utopias can be seen as a wild and flourishing bush separating into different branches with relative autonomy, creating chains of intertextual discussions between works yet inevitably intertwining with other branches of utopian tradition.

Such complications and intertwinements concern the disciplinary domain of interest, with More’s Utopia being simultaneously a fictional text and political satire and the text inspiring literary works and political programs. Consequently, utopia requires an interdisciplinary approach that considers the utopian form’s political and literary developments while respecting the specificity of political and literary productions. In literature, another complication stems from the relationship of utopia to other genres, most notably sci-fi. While utopias and sci-fi emerged as distinct genres, they increasingly became so close that the researchers working in utopian studies see sci-fi as a subgenre of utopia, and sci-fi scholars consider utopia a subgenre of sci-fi. Outside utopias in the narrow sense, the utopian impulse was recognised by Ernst Bloch as an essential element of everyday life, from advertising to architecture. Utopias seem to spread out from their relatively stable beginning and permeate modern culture even in surprising spaces.

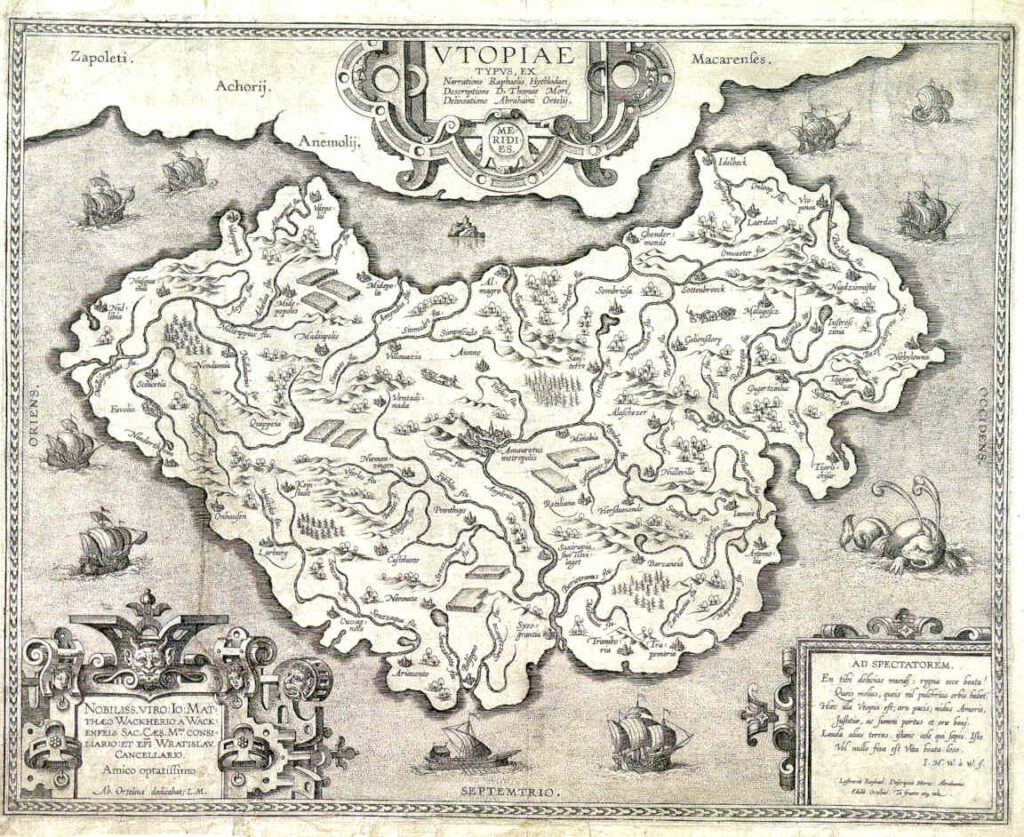

Leaving aside Bloch’s utopian impulse and focus more narrowly on utopian texts or programs, one could characterise utopia as a vision of society that is qualitatively radically different from ours. Jameson defines the utopian form as “a combination of closure and system, in the name of autonomy and self-sufficiency and which is ultimately the source of that otherness or radical, even alien, difference”. (Jameson 2005: 5) Throughout the history of utopia, this construction has met with significant changes that often reflect broader societal and cultural developments. One such change concerns the nature of the utopian separation from the modern world. In More’s book, this separation had a spatial nature. The first action that King Utopus performed when establishing the new society was cutting the fifteen-mile-wide channel destined to isolate Utopia from its neighbours. (More 1989: 43) As Fátima Vieira explains in her article “The Concept of Utopia”, following the development of the idea of progress in the late eighteenth century, utopias have turned from a place in our world to a point in time situated in the future (Vieira 2010: 9), making spatial separation redundant. Gradually, as we have become more accustomed to seeing the present as a point in a progressive trajectory leading to something better, utopias became synonymous with visions of the future, resulting in the overlap between sci-fi and utopias mentioned above.

Significantly, historical and political developments of modernity also influenced the views with which people approached utopian visions, leading to the development of various subgenres: utopia was not always seen as the desired “good place”: satirical utopists of the eighteenth century mocked the utopian aspirations of their predecessors, while dystopias highlighted the dangers inherent in utopian plans. At the same time, anti-utopists such as George Orwell expressed their utter disbelief that a utopian change could do any good to society. Anti-utopianism became increasingly characteristic of twentieth-century literature. This development can be understood as a sign of a crisis of positive utopian thought that was a result of the way utopias have intertwined with the totalitarian regimes of communism and nazism, leading Karl Popper in The Open Society and its Enemies (1994) to declare that “the Utopian attempt to realize an ideal state, using a blueprint of society as a whole, demands a strong centralized rule of a few, and which therefore is likely to lead to a dictatorship.” (Popper 1994: 149) Despite these somber pronouncements, utopias have gained a new breadth in the second half of the twentieth century, with feminist, queer, and ecological utopias using the form to concretely imagine positive developments in areas usually overlooked by traditional utopists. Significantly, as Zsolt Czigányik argues in the introduction to Utopian Horizons: Ideology, Politics, Literature (2017), the association of utopianism with totalitarian rule made the mistake of substantially narrowing the sphere of utopia to one of its historical realisations and overlooking the ambivalence inherent even in the most optimistic utopian constructions.

Between a plan and a daydream: More’s Utopia

More’s Utopia shows that this ambivalence was present in utopia since the concept was coined. One may register it already in the title of the book and the name of the place imagined by More: the term “utopia”, as pronounced in English, can suggest two Ancient Greek etymologies: outopia (the “non-place”) or eutopia (the “good place”). To make it clear that this riddle does not have any simple solution, the paradox is explicitly thematised in a poem (presented in the appendix of the book), where both meanings are given some justification:

“No-Place was once my name, I lay so far;

But now with Plato’s state I can compare,

Perhaps outdo her (for what he only drew

In empty words I have made live anew

In men and deeds, as well as splendid laws):

‘The Good Place’ [Eutopia] they should call me with good cause.” (More 1989: 123)

Out of these alternatives arises a broader paradox that can lead to two different possible interpretations of utopia: the imagined society can be read as the good place, a vision of how the society should work, or a no-place, a mere product of imagination that is not to be taken too seriously, at best as a satiric reversal of existing society.

This principal tension can also be described as a tension between the two books of Utopia. The first book introduces a conversation between three men: the first-person narrator identified as More himself, his friend Peter Grand, and a certain Raphael Hythloday, presented as a travelling philosopher, who gradually overtakes the central part of the conversation and serves as the narrator of the second book, comprising of a travel narrative to a place in the new world called Utopia. The name Hythloday introduces the first of many subtle hints through which the author signals his distance regarding the contents of the travel narrative: in ancient Greek, hythloday means one who speaks nonsense. When emphasising the first book, the satirical function of the text becomes the centre of attention: Hythloday’s critique of England’s penal and economic system becomes the fundamental issue, and from this view, the travel narrative can be read just as an argument pointing to England’s fundamental flaws. By, on the other hand, foregrounding the utopian travel narrative, the surrounding conversation may become just a strategy to make the radical message of the second book more politically palatable.

As presented in the travel narrative, Utopia is an island with a deeply rational societal organisation. The main structural element of this organisation is the abolition of money, from which most other principles can be explained. In the context of utopias, Fredric Jameson interprets the existence of such an organising principle in the context of broader society as the utopian enclave, suggesting that at some point in the development of our civilisation, some aspects of our society are not fully reified and can be imagined differently. Jameson suggests that the “Utopian space is an imaginary enclave within real social space” (More 1989: 15), describing it as “a pocket of stasis within the ferment and rushing forces of social change, which may be thought of as a kind of enclave within which Utopian fantasy can operate.” (More 1989: 15). In More’s case, such an enclave was open only so far as his society was not yet based on capitalist logic, and money had not yet become the organising principle of society.

More imagines Utopia as a society functioning without the principle of private property: housing and land are rotated among the citizens, with every citizen having to exchange housing regularly and move from the city to the countryside and back. The abolition of money is also highlighted in Utopians exercising devaluation of traditional symbols of wealth: utopians wear simple clothes and mock their visitors from abroad who arrive in elaborate costumes. To show their lack of interest in gold, which is inferior to iron as it has no practical utility, they

“eat from earthenware dishes and drink from glass cups, finely made but inexpensive, while their chamber pots and all their humblest vessels […] are made of gold and silver. The chains and heavy fetters of slaves are also made of these metals. Finally, criminals who are to bear the mark of some disgraceful act are forced to wear golden rings in their ears and on their fingers […].” (More 1989: 63)

Because of the rational distribution of resources and work, everyone must work only six hours daily. Along with measures that would be recognised as progressive even today, such as the distribution of work tasks among men and women alike or religious tolerance, the Utopian societal system also includes some darker overtones: slavery, draconic punishments for sexual contact before marriage, and importantly, what Jameson calls a “machiavellian foreign policy”. The fundamental enclosure of the utopian society from the outside necessary for the total and systematic enactment of the utopian ideals means that such ideals only apply within the chosen community.

If the provisions of the organisation of a utopian society seem absurd, the frame narrative, where Hythloday speaks of England, does not portray it as a much less ridiculous place. England is here represented as a country ruled by the conspiracy of the rich and powerful. A telling example of this is Hythloday’s satirical description of contemporary practices of sheep herding:

“«Your sheep», I replied, «that commonly are so meek and eat so little; now as I hear, they have become so greedy and fierce that they devour men themselves. They devastate and depopulate fields, houses, and towns. For in whatever parts of the land sheep yield the finest and most expensive wool, there the nobility and gentry, and yes, even some abbots and though otherwise holy men, are not content with the old rents that the land yielded to their predecessors. Living in idleness and luxury without doing society any good no longer satisfies them; they must do positive evil.»” (More 1989: 19)

The higher classes can drastically worsen ordinary people’s living conditions just so they profit more from a fashionable type of wool, making sheep more valuable than people in practice. It is also a country where people are not given sufficient means to obtain basic needs such as shelter, food, and warmth even when they work 14-hour days and then are punished by death for stealing simple means of existence. Utopia is deeply critical of the feudal order that encourages profound inequalities and makes whole countries dependent on the whims of kings who endlessly prove their worth in battles instead of governing their own lands. By showing us the absurd and strange institutions of Utopians, More’s utopia enacts (to turn to Jameson’s terminology once again) a utopian estrangement of contemporary conditions.

In Hythloday’s narrative, Utopia is the example of the best societal organisation, whereas England is the example of the worst. Hythloday’s narrative, however, does not stand on its own but is presented as a reported speech by a person who came out of nowhere and, contrary to the suggestions of his partners in dialogue, is not willing to put his experiences to practical use in court politics by advising princes and kings. When they discuss the matter further, his interlocutors agree that had he shared his ideas about the perfect society directly, they would have “turned deaf ears to him” (More 1989: 36). But why not influence the king at the cost of making Hythloday’s ideas a little less radical? For Hythloday, however, such compromise is unimaginable, as current institutions are founded exactly on the principles of private property, in stark opposition to the utopian ones. Attempts to find common ground would inevitably fail: “Either they will seduce you, or if you remain honest and innocent, you will be made a screen for the knavery and folly of others.” (More 1989: 35). And so, Utopia remains as it is: an imperfect invention of an individual, retaining its purity and radicalness at the cost of political efficiency. The first-person narrator himself concedes at the end of the second book that while in Utopia, there are “many features that in our own societies [he] would like rather than expect to see” (More 1989: 111), “quite a few of these laws and customs [Hythloday] had described as existing among the Utopians were really absurd.” (More 1989: 110)

Far from being a straightforward political program, Utopia is a self-reflexive text that explores not only the positive utopian program but also reasons for caution. As such, Utopia can be read as including grains of satire, distrust, and scepticism that, in history, eventually grew into the genres of satirical utopia and dystopia. The tensions between utopia and satire, between eu-topia and ou-topia, between the first and the second book can never be fully resolved in favour of one or the other option but should be accepted as an ambivalence of the form itself. Instead of considering any moderate improvements to the current order, utopias ask us to leap into radical otherness, to open our imagination to a fundamentally different world and, through this “non-place,” perhaps gain a new and different perspective on “our place.” Instead of communicating the model of society as an object of a political strategy to a monarch, More gives us Utopia, the book, a cultural object that necessarily provokes reactions: Perhaps this all is just a hilarious daydream not to be taken seriously. Perhaps the project was fundamentally flawed from the start, its founding principle leading to totalitarianism. And perhaps there could be another utopia, designed just a bit better to fix this or that flaw in the system…

Bibliography:

Fátima Vieira, “The Concept of Utopia”, in Gregory Claeys (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Utopian Literature, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010, pp. 3-27.

Fredric Jameson, Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions, New York, Verso, 2005.

Karl Popper, Alan Ryan and Ernst H. Gombrich (eds.), The Open Society and Its Enemies, Princeton, University Press, 1994.

Thomas More, George M. Logan and Robert Adams (eds.), Utopia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Zsolt Czigányik, “Introduction – Utopianism: Literary and Political”, in Zsolt Czigányik (ed.) Utopian Horizons: Ideology, Politics, Literature, New York, Central European University Press, 2017, pp. 1-17.

Iconographic apparatus:

Immagine 1: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utopia_%28More_book%29#/media/File:Utopia.ortelius.jpg